The impact of new power geopolitics on cybersecurity: how can lean teams react

Navigating cybersecurity amidst rapid geopolitical shifts: strategies for lean teams

The first quarter of 2025 has ushered in a series of unprecedented geopolitical shifts. Long-standing allies are now entangled in escalating trade wars, with markets plummeting under increasing tariffs and businesses struggling to keep up with unpredictable US economic policy. At the same time, the European Union is embarking on a significant rearmament initiative, aiming to reduce its reliance on US military support. Meanwhile, the United States is aggressively pursuing an end to the Ukraine conflict, aligning its diplomacy more closely with Russia and threatening traditional alliances.

These developments signal a return to classical power geopolitics, where nations vie for influence and control over strategic assets using military and economic power as the primary driver of global affairs. The days of soft power diplomacy, where countries leverage non-military tools - such as culture, diplomacy, media, education, and economic incentives - to shape international relations and exert influence, seem to be gone. More critically, they highlight a new era where historically significant events unfold at an unconventionally accelerated pace, challenging the adaptability of global industries and individual countries.

For the cybersecurity industry, the effects of these developments are significant: over the past 15 years, cybersecurity leaders have had to focus primarily on rapid technological advancements. This was because technology, not geopolitics, moved faster. Geopolitics largely influenced regulatory changes, but these shifts were gradual and manageable. Today, however, the pace of geopolitical change with a direct impact on cybersecurity is accelerating so fast that cybersecurity leaders wonder how they can keep up.

Keeping up sustainably

Rapid geopolitical changes are already affecting the cybersecurity industry. For instance, the US’s diplomatic shift toward Russia has led to an executive order halting all cyber-offensive operations against the Russian Federation. Such change in policy raises questions as to whether the pause will yield counterproductive outcomes, emboldening adversaries to exploit perceived vulnerabilities.

In this volatile environment, lean cybersecurity teams face challenges compared to teams in larger organisations. Large security teams can integrate digital security with physical security and threat intelligence, giving them the scaled intelligence tracking capabilities needed to adapt to rapid geopolitical shifts. In particular, organizations that have unified these functions under a Chief Security Officer will be well-positioned to navigate this dynamic landscape.

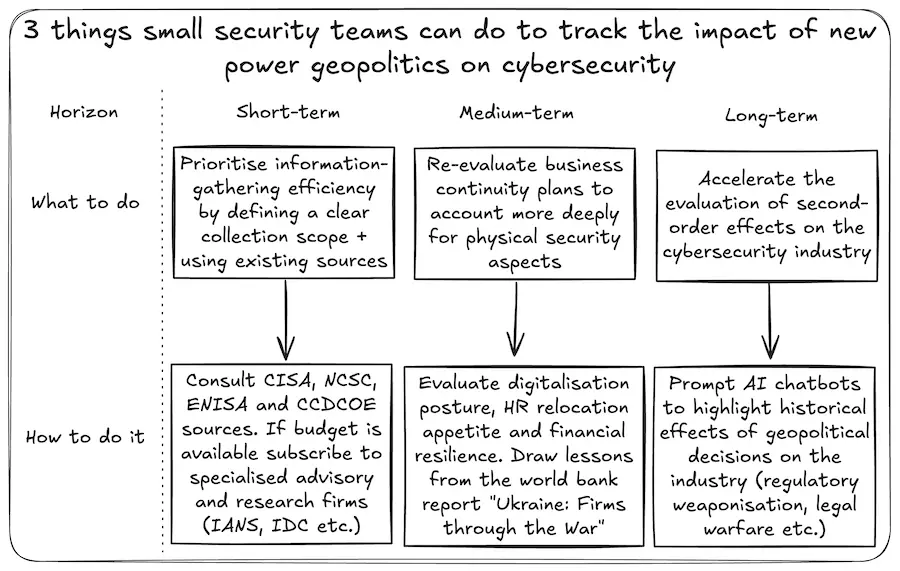

Conversely, small and medium-sized enterprises will not have the luxury of large, well-integrated security teams. To keep pace, leaner security functions must aggressively prioritise information-gathering focus and efficiency. Teams should define clear objectives, focusing on geopolitical events that directly influence cybersecurity regulations, such as trade disputes, while deprioritizing unrelated developments like changes in military spending.

Leveraging resources from government and international bodies should be the first port of call for lean teams. Publications from agencies like the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, and the NATO Cyber Centre offer trusted, ready-made insights that can be rapidly assimilated by smaller teams.

For teams with available budgets, subscribing to specialized advisory and research firms, such as IANS research, can be advantageous. These firms provide actionable insights through peer-driven knowledge, offering in-depth reports, roundtables, briefings, and consulting services. More importantly, subscribers can access networks of seasoned practitioners and subject matter experts, facilitating direct inquiries about the implications of geopolitical events on cybersecurity. Such research firms will connect small security teams with worldwide experts to source advice on handling the cybersecurity impact of geopolitical events. Additionally, they typically offer daily email briefings to keep teams informed about relevant developments.

Re-evaluate business continuity plans

European rearmament efforts risk decoupling the EU from US protection, potentially bolstering self-defence initiatives on the continent. If the situation deteriorates - for example, if a Ukraine peace deal fails leading to intensified hostilities - organizations with personnel in the Baltic states or Central Europe must contemplate employee relocation strategies.

In anticipation of such scenarios materialising, small teams should re-evaluate business continuity plans to account more deeply for physical security aspects. Considerations should include employee mobility, remote work capabilities, and the organization’s willingness to provide financial relocation support. These issues should then be discussed with management to update overall business continuity management (BCM) strategies.

Smaller security teams can draw lessons from recent history. The World Bank’s report titled “Ukraine: Firms through the War” offers valuable insights into the physical security aspects of relocating business operations from European conflict zones. Notably, three findings are particularly relevant:

-

Digital Transformation: Digital tools and technologies significantly aided businesses in adapting to new realities. A digital-first posture enhanced resilience and provided firms with alternative operational avenues during disruptions. For lean teams, this provides evidence to lobby management to evaluate the true digital mobility of their workforce. While the pandemic accelerated remote work capabilities, firms with operations tied to physical facilities must carefully consider relocating both operations and staff in cases of land conflict and displacement.

-

Human Resource Management: The report highlights how despite a 53% average decline in sales, employment saw a comparatively smaller reduction of 26%. This suggests that affected firms prioritized retaining employees, recognizing the value of human capital in maintaining operations and facilitating post-crisis recovery. However, in cases of larger and more sustained displacements, it’s highly possible that the same human capital retention may not be possible. Security teams should challenge management to think beyond traditional business continuity (i.e., maintaining operations) and consider the logistical and financial aspects of employee relocations, assessing the organization’s long-term commitment to supporting its workforce.

-

Financial Management and Access to Capital: More interestingly, access to finance emerged as a significant challenge, with many firms facing financial constraints. The need for financial assistance and improved regulatory frameworks highlighted the importance of robust financial planning and the ability to secure capital during crises. With geopolitical events now causing ruptures in traditional alliances, management teams need to start thinking not just in terms of business continuity, but also in terms of financial resilience. On this front, lean teams should push management to think about financial redundancy and access to capital in crises, possibly by restructuring corporate entities and building separate financial coffers across continents.

Using AI to discover second-order effects

Rapid US diplomatic shifts may have medium to long-term consequences that are hard to foresee. For example, escalating trade wars may lead to unintended outcomes, with nations potentially weaponizing regulations, disrupting supply chains and increasing nationalistic cyber policies. In 2010, China restricted exports of rare earth metals to Japan following a maritime dispute.

The restrictions affected elements essential for electronics, defence products, and various high-tech applications. The United States, EU, and Japan contended that these restrictions violated World Trade Organization (WTO) regulations. In 2012, the US filed a case with the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body which, by 2014, led to the removal of export quotas. This dispute prompted increased investment in rare earth production outside of China.

Similarly, in 2023, China imposed export licensing rules on gallium and germanium, essential for semiconductors, in response to US tech restrictions. Affected businesses were forced to obtain a dual-use item export license to provincial commercial departments, prompting huge reassessments of procurement plans globally.

Although Europe has not yet experienced similar scenarios, the EU possesses the capability to leverage regulations to heighten trade barriers. For instance, in 2023, the EU introduced the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), a carbon tariff taxing imports like steel and aluminium based on their carbon emissions. Critics viewed it as a covert trade barrier targeting nations reliant on coal-heavy energy. Think tanks predicted that the CBAM would have second-order effects such as welfare losses, deteriorating terms of trade, and marginal wage decreases in non-EU countries. The US and China opposed aspects of the mechanism, deeming it unfair.

Analyzing second-order effects is crucial when assessing geopolitical changes. AI chatbots can assist lean teams in this task by suggesting potential outcomes of geopolitical changes in the cybersecurity industry and providing historical examples of such effects. Such tools can help accelerate the evaluation of second-order effects and the likelihood of scenarios impacting their firms and industries.

Conclusion

The accelerating pace of geopolitical changes presents new challenges for cybersecurity leaders. The intersection of trade wars, military rearmament, and shifting diplomatic alliances demands that organizations remain agile and well-informed. Large firms with integrated security teams are better positioned to navigate this landscape, while smaller teams must refine their information-gathering strategies. Leveraging government resources, advisory firms, and AI-driven analysis will be crucial in anticipating second-order effects. Finally, business continuity strategies must be reassessed to account for potential disruptions in key regions.